Software-Mediated Drum Circle

Here’s a rough sketch for a software-mediated drum circle. This could be a good fit for Burning Man, a music festival, or similar settings.

I came up with this idea back in 2014. I wanted to reconcile two competing aspects of the typical live electronic music experience. On the one hand, I know (like any promoter) that it’s headliners who sell tickets. But on the other hand, I wanted a new way to understand live performance which would counteract the concept of the superstar DJ and focus instead on communal experience.

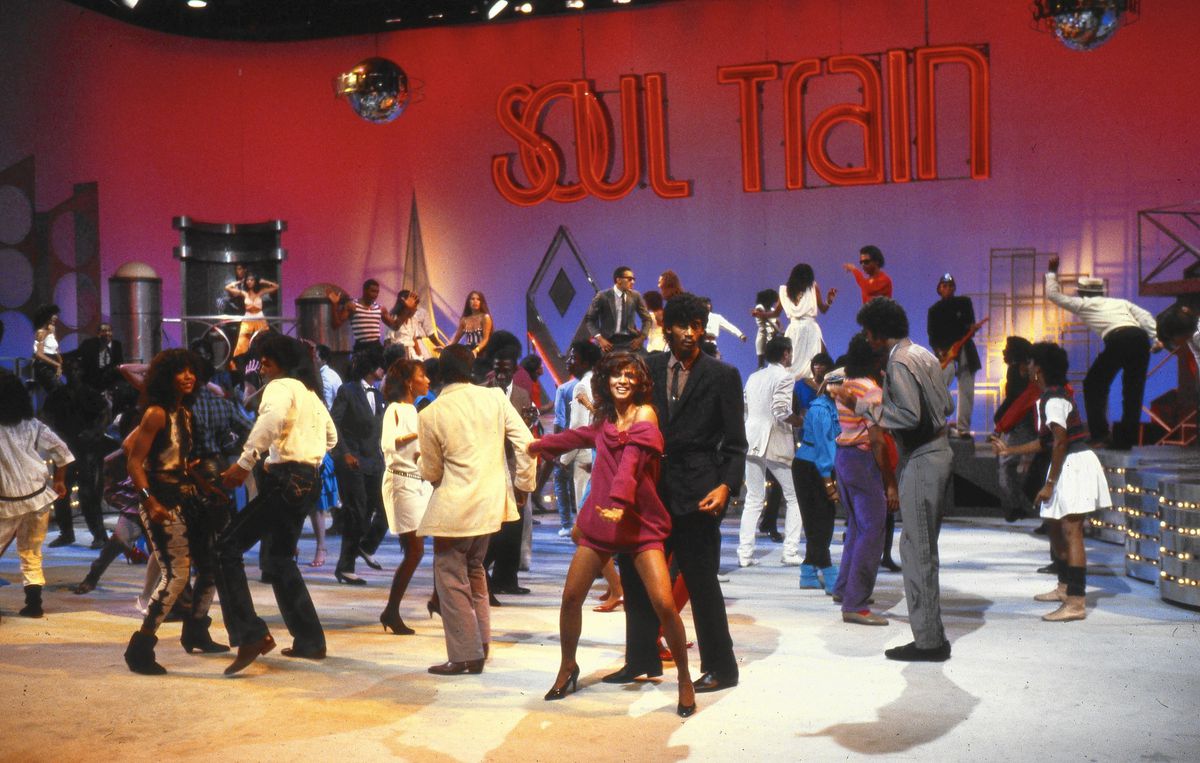

There’s inherent tension to these two forces. When superstar DJs make any kind of sense, it’s because better musicianship results in better music. On the other hand, a musical experience where dancers interact with each other is very different, on an emotional and spiritual level, from one where everybody stares at the superstar.

And, while big stadium DJs often just play their own music, there’s another school of thought around DJing which treats reading the crowd, and letting that reading guide your track selection, as an essential part of the experience. In this model, a DJ doesn’t just perform, they also sort of facilitate collaboration. To be fair to the stadium DJ, however, it’s a lot easier to read a crowd when that crowd is not unimaginably large and stretching so far into the distance that you cannot possibly see everyone’s face. So another way to look at it is to say there’s a spectrum, from a party to a show.

Either way, I wanted to reconcile these two somewhat oppositional tensions, and I also had a simpler goal: to find a way to use modern technology to make live electronic music performance more exciting than watching some dude poke at his laptop, without moving too far down towards the show end of the party/show spectrum.

My idea was to leverage user-generated visuals and software-enabled audience participation.

By user-generated visuals, I mean that in addition to using the MIDI signals from an electronic drum pad or drum kit to create music, you can also use those same signals to drive visualization software as well or instead. I built some software in Clojure along these lines. The code is on GitHub.

Here’s a quick video demo I recorded back in 2014.

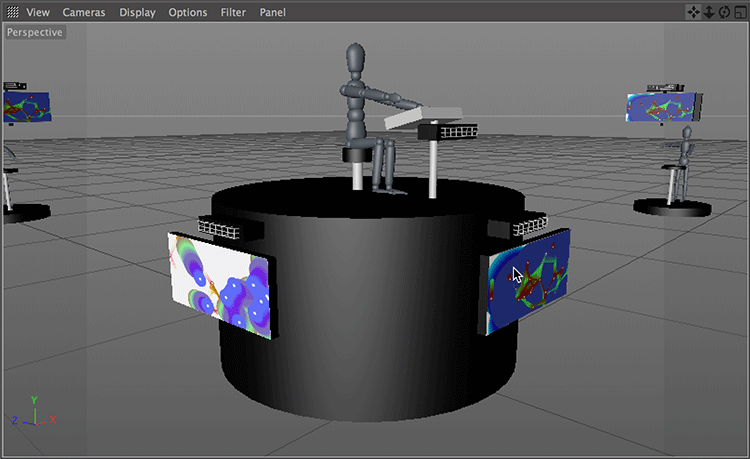

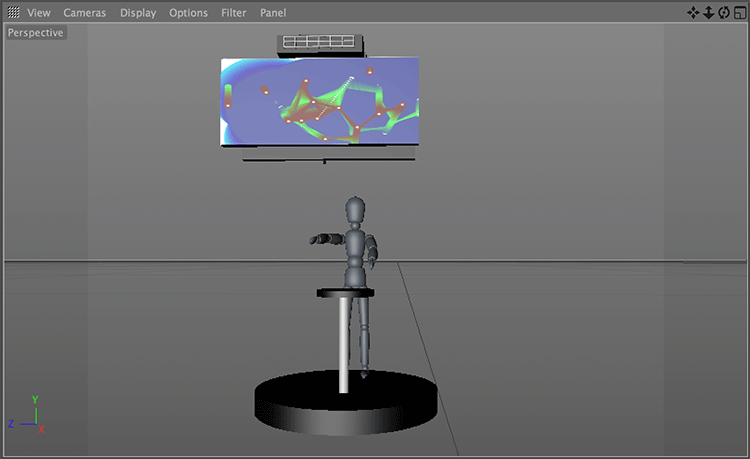

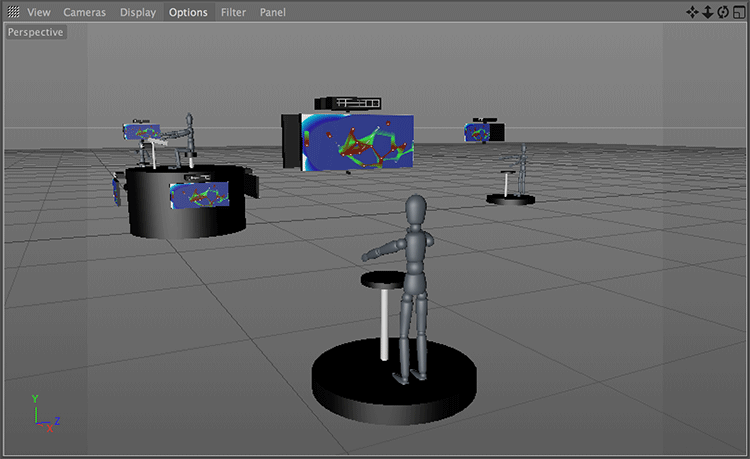

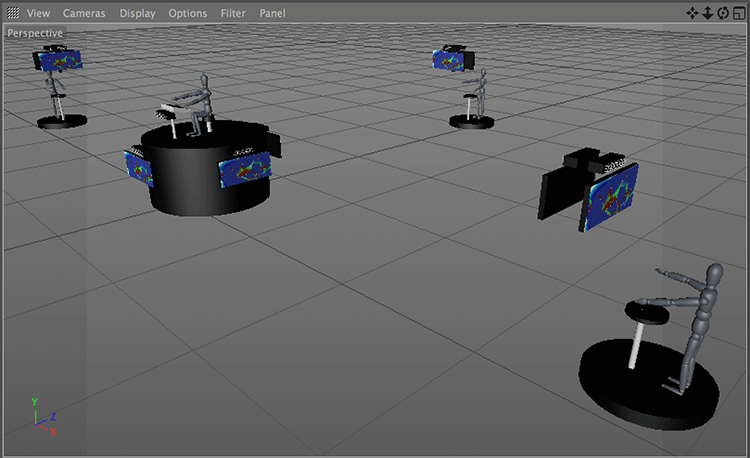

Anyway, what I envisioned was a raised drum platform at the center of the venue, with video screens and concert lighting attached. The video screens would plug into software which accepted MIDI input from the electronic drums, so that the musician could also function as a VJ, or in collaboration with a VJ (who could choose to process the MIDI input through any visualization software which accepted MIDI).

There’s a fun irony here: putting the performer in the center of the venue de-centers them in terms of the experience. It pulls the experience closer to the party end of the party/show spectrum. Because if you’re behind the performer, and they have their back to you, but you’re surrounded by dancers, you might just turn around and interact with the dancers instead.

Anyway, throughout the room, you would also have a drum circle of MIDI-enabled drums, which would not necessarily create any sound, but which would drive visualizations on screens nearby. Sound would be optional; vision would be the key. These drums would go on smaller raised platforms, probably enclosed in “audience participation pods” for security, and to simplify managing them during the event.

That could work a lot of different ways. Maybe audience members buy tickets, or take turns. Maybe it’s not audience members in the pods, but percussionists; you could use this system to distribute a band throughout a venue in a way that could never have happened without modern technology, or you can use it blur the boundaries of audience and performer, creating a new intermediary group which is a little bit of both.

The visualization software which the pods control could be as goal-oriented and structured as music games like Guitar Hero, Rocksmith, and Beat Saber, but what I envision here (and even built a prototype of, per the above video) is more freeform, artistic material designed to encourage creativity and spontaneity. Likewise, these pods could send the MIDI that they capture from the audience to the main performer, or to a VJ working with the main performer, who could process it in real time. Capturing audience movement data in this way, and integrating it with the performance visuals, makes this more of a communal experience to share, and less of a staged spectacle to consume.

Either way, with the hardware all in one place, it’s easier to manage. It’s also easier to distribute the pods throughout the venue. They could be very close to the main performer, or quite far. You could have four of them, as in these rough sketches, or forty, or four hundred. (Also, the main performer wouldn’t need to be a drummer, necessarily. They could be a DJ, or a band.)

Dispersing these drum pods throughout the venue means that the crowd gets several additional areas of local focus. If this were a concert design, the new areas of focus might just host video displays, showing you the main performer and reinforcing their centrality. Instead, it de-centers the main performer.

The drum pod plays a more local role, creating visuals which may communicate back to the main performer but which definitely display in front of the nearby audience members. And the drum pod is optional. In a stadium crowd where thousands of other people are staring at a performer, you’re going to turn your head in the same direction. If you’re in the middle between the main performer and the audience participation pod, you can turn your attention to either of those focal points, or to the people around you.

This design can restore party factors to shows, and give you some control and self-determination in positioning your event on the party/show spectrum. If you want a big party with a performer in the middle who most people don’t even realize is there, you set up a lot of audience participation pods, and you make the central “stage” pretty modest. If you just want to sprinkle some magic party dust on top of a big show, you keep a big, stadium-style stage, but you add a few drum pods here and there, and you staff them with trained professionals instead of opening them up to audience members. To crank the hippie factor up to 11, have the drum pods contribute not just visualization MIDI but audio from the drums as well. To present a flawless, rehearsed performance, restrict the drum pods to visualization only, and have a VJ or team of VJs carefully curate any visualization MIDI which the drum pods contribute.

Any given event will have its own preferred blend of party factors and show factors. Big music festivals today often crank both factors up to 11. This system is a framework that can work well in multiple different contexts.